Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH) / Enlarged Prostate

Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH) / Enlarged Prostate

WHAT IS BENIGN PROSTATIC HYPERTROPHY (BPH)?

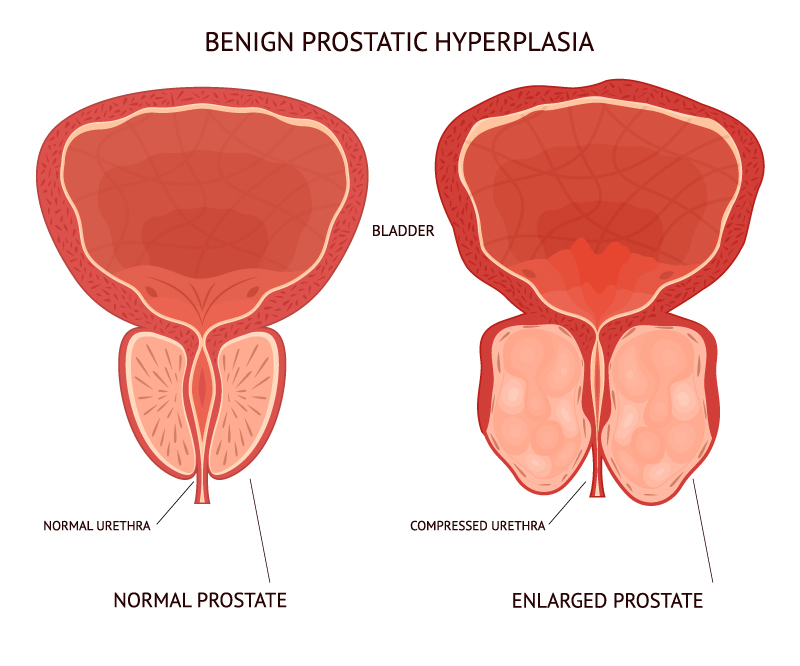

The prostate, part of the male reproductive system, is a walnut-sized gland that makes the seminal fluid for carrying sperm. It is located behind the base of the penis, in front of the rectum, and below the bladder. It surrounds the urethra, the tube-like channel that carries urine and semen through the penis.

Benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH) is a blockage of the urethra caused by an enlarged prostate. A common condition associated with growing older, BPH has not been associated with a greater risk of having prostate cancer. BPH affects about 50% of men by age 60, and 90% of men by age 85. If left untreated, BPH can lead to blood in the urine (hematuria), incontinence, kidney stones, infection, inability to urinate with damage to the bladder, and kidney damage.

The prostate, part of the male reproductive system, is a walnut-sized gland that makes the seminal fluid for carrying sperm. It is located behind the base of the penis, in front of the rectum, and below the bladder. It surrounds the urethra, the tube-like channel that carries urine and semen through the penis.

Benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH) is a blockage of the urethra caused by an enlarged prostate. A common condition associated with growing older, BPH has not been associated with a greater risk of having prostate cancer. BPH affects about 50% of men by age 60, and 90% of men by age 85. If left untreated, BPH can lead to blood in the urine (hematuria), incontinence, kidney stones, infection, inability to urinate with damage to the bladder, and kidney damage.

What can cause BPH?

Risk factors for BPH include aging and a family history of the condition. The prostate gland generally starts to enlarge around age 40. Men’s testosterone levels drop, but they continue to produce high levels of a hormone called dihydrotestosterone (DHT). DHT has been linked to prostate growth. The enlarged prostate can then block urine flow, making the bladder push harder. The bladder may be unable to empty, leading to urinary retention and overflow incontinence.

Certain medications, such as those used to treat allergies and beta-blockers used to treat hypertension, can worsen BPH symptoms. A sedentary lifestyle can also worsen BPH symptoms, while increasing exercise can help relieve them. Avoid alcohol and caffeine, which can worsen BPH symptoms. The risk of BPH can be decreased through maintaining a healthy weight, eating a healthy diet that includes fruits and vegetables, and staying active to regulate weight and hormone levels.

What can cause BPH?

- A bladder that feels full, even right after urinating

- Frequent urination

- A sudden, uncontrolled need or urge to “gotta go” urinate

- Weak urine flow

- Dribbling of urine

- The need to stop and start urinating several times

- Trouble starting to urinate

- The need to push or strain to urinate

- Getting up at night to urinate more than 2 times

How is BPH diagnosed?

- Medical History. Tell your health care provider about your symptoms, how long you’ve had them, and how they affect your everyday living. Bring a list of your over-the-counter and prescription drugs. Tell your provider about any past and current health problems and about your diet, including how much and what kinds of liquids you drink during the day and night.

- Physical Exam. A health provider will often feel your abdomen, the organs in your pelvis, and your rectum, to see what may be causing your symptoms.

- Blood tests. A PSA blood test will screen for prostate cancer.

- Urine Test. A sample of your urine may be taken to test for infection or blood.

- Post-void residual volume (PVR). This test measures the amount of urine left in the bladder after urination. It can be measured by catheterization or non-invasively by ultrasound.

- Uroflowmetry. This test measures how fast urine flows, how much flows out, and how long it takes.

- Ultrasound of the prostate. This non-invasive procedure measures prostate volume or size.

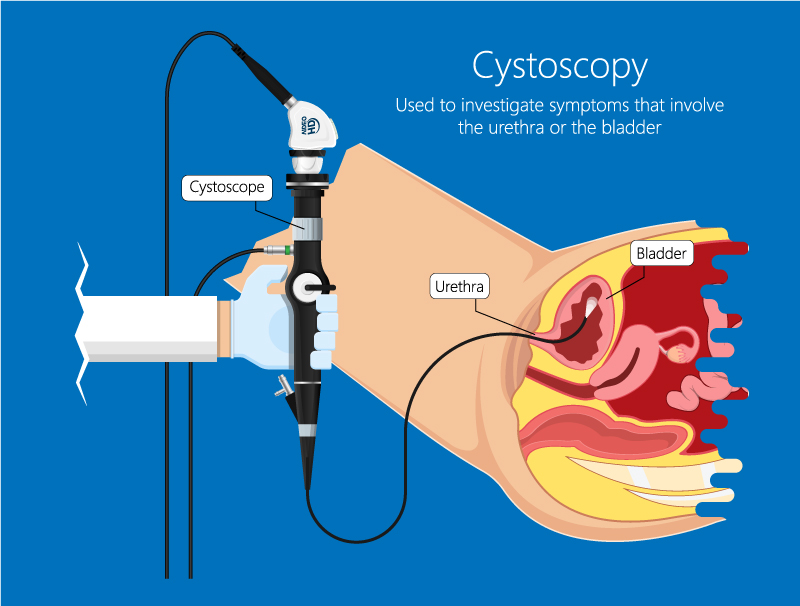

- Cystoscopy and Urodynamics. In cytoscopy, a hollow tube called a cystoscope is inserted into the urethra (the tube that carries urine out of the body) and then into the bladder. The lens in the cystoscope allows a doctor to examine the bladder lining. In urodynamics, a series of tests measures lower urinary tract function. These tests reproduce a person’s voiding patterns to help identify any underlying problems. One of the most important measurements obtained is the pressure inside the bladder and kidneys.

How is BPH treated?

- Medications. BPH can be treated with two types of medications, usually used in combination. Alpha-blockers relax the smooth muscle of the prostate gland to help open the urine channel. These can include Cardura, Cialis, Hytrin, Flomax, Rapaflo, or Uroxatral. Another type of medication, 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors, block the production of DHT to help shrink the prostate. These can include Avodart or Proscar.

- Transurethral Resection of the Prostate (TURP). This minimally invasive procedure is the prostate surgery most commonly used to treat BPH. Using a camera, the surgeon removes prostate tissue blocking the urethral channel. Patients usually go home the same day, with a catheter or tube in the bladder. Risks and complications include bleeding, fluid absorption, low sodium (hyponatremia), incontinence, and (very rarely) erectile dysfunction.

- Photoselective Vaporization of the Prostate (PVP). This surgery generally carries less risk than TURP. A laser is used to vaporize prostate tissue. Risks and complications include the need for blood transfusion, fluid absorption, low sodium (hyponatremia), incontinence, and (very rarely) impotence.

- Rez?m Therapy releases natural water vapor throughout the targeted prostate tissue. When the steam contacts the tissue and turns back into water, it releases energy, killing the excess prostate cells that squeeze the urethra. Over time, the body’s natural healing response absorbs the dead cells and shrinks the prostate. Bleeding from the prostate may occur, and a catheter might be needed for several days.

- Other minimally invasive therapies. These are usually done in the office or as an outpatient procedure, followed by 5 to 7 days of catheterization.

· UroLift® implants. Delivered through the urethra, these implants hold the enlarged prostate tissue out of the way so it no longer blocks the urethra.

· Transurethral needle ablation (TUNA). Delivered through needles, radiofrequency waves heat and destroy prostate tissue.

· Transurethral microwave therapy (TUMT). This procedure uses microwaves to harden prostate tissue. The treated parts of the prostate are then either absorbed by the body or they pass with urine.

· Interstitial laser coagulation of the prostate (ILC). This procedure uses lasers to vaporize prostate tissue. - Simple Prostatectomy. This surgery requires hospitalization and a drainage tube (called a Foley catheter) that will remain in place from 2-7 days. This procedure is used when the prostate has grown very large (over 80 grams), causing urinary retention. The surgery may be done in three ways:

· Open Retropubic Simple Prostatectomy. Through an incision, the surgeon moves the bladder aside, cuts into the prostate, and removes the blocking core of the gland. The prostate capsule is then closed.

· Open Suprapubic Simple Prostatectomy. The surgeon makes an incision in the lower abdomen, then opens the bladder to remove prostate tissue through the bladder.

· Robotic Simple Prostatectomy. The surgeon makes 5 small incisions in the abdomen. Cameras and surgical instruments are put into the holes to help the surgeon remove the enlarged prostate core blocking the urethra. The core is removed through one of the small holes in the abdomen.